|

Wampum Belt Archive

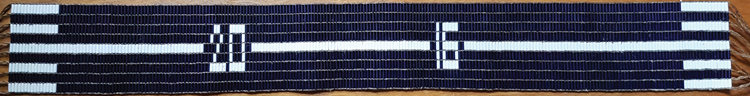

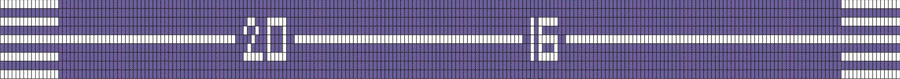

Peskotomuhkati - Canada Belt

Reaffirmation 2016

The wampum was made by Haohyoh Ken Maracle of the Deer Clan (Cayuga Nation of the Haudenosaunee) at the Grand River Territory. Glass beads have been common substitute for if shell wampum was not available since the 18th century.

R. D. Hamell November 15 2024

Original Size: |

Columns: 231. Rows 9. Glass Beads |

Reproduction: |

Beaded Length: 36.7 inches. Width: 4.5 inches. Length w/fringe: 60.0 inches. |

Beads: |

Columns: 231. Rows: 9. Total beads: 2,079 beads. |

Materials: |

Warp: Deer leather. Weft: Artificial sinew. Beads: Glass. |

Description:

2016: The New Wampum: Respect, Trust and Friendship

In May, 2016, at Qonasqamkuk, representatives of the Governments of Canada and New Brunswick met with the Peskotomuhkati Council. Though this was before any formal mandate to negotiate, the three governments agreed that the principles of the existing treaties between the Peskotomuhkati Nation and the Crown would continue to guide and govern their relationship.

The principles are those of the Covenant Chain: respect, trust and friendship.

At the same meeting, the three governments agreed that it would be proper, before any new negotiations began, and to begin to accomplish what Prime Minister Trudeau set out in his mandate letters to the Ministers of Indigenous Affairs and Justice – “restoring respectful nation to nation relations” – that the existing treaty relationship should be formally reaffirmed.

It is the 250th anniversary of Joseph Goreham’s Instructions to reaffirm the treaties of the 18th century, and to extend the Covenant Chain to the Wabanaki Nations. To commemorate the reaffirmation of the treaties in 2016, the Peskotomuhkati Council commissioned the making of a new wampum belt.

The wampum was made by Haohyoh Ken Maracle of the Deer Clan (Cayuga Nation of the Haudenosaunee) at the Grand River Territory. It is made of glass beads of a kind that have been in use as a substitute for shell wampum since the 18th century.

The white line from end to end of the wampum symbolizes the clear path of honest, open communication between the partners – brother nations – in the relationship. The four white strips at each end remind us that the Peskotomuhkati Nation is part of the Wabanaki Confederacy, and at the reaffirmation ceremony, Mi’kmaq, Maliseet and Penobscot representatives fulfill their duty as witnesses to shared relations. The year 2016 places this ceremony in time, but also recalls that it confirms past reaffirmations.

In giving this new wampum to the Government of Canada, the Peskotomuhkati Council has created a new symbol to fulfill a role in an ancient process.

The federal negotiator, the custodian of the wampum, will bring it to each meeting between the three governments. The belt will be handed to the Peskotomuhkati speaker, who will then be responsible for opening the council in accordance with tradition, by giving thanks to the natural world, and by welcoming the federal and provincial representatives to Peskotomuhkati territory. The presence of the wampum will mean that the work of restoring respectful nation-to-nation relations is in progress.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has explained:

Historically and, to a certain degree, even at present, Indigenous ceremonies that create community bonds, sanctify laws, and ratify Treaty making have been misunderstood, disrespected, and disregarded by Canada. These ceremonies must now be recognized and honoured as an integral, vital, and ongoing dimension of the truth and reconciliation process.

Ceremonies also reach across cultures to bridge the divide between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples. They are vital to reconciliation because of their sacred nature and because they connect people, preparing them to listen respectfully to each other in a difficult dialogue. Ceremonies are an affirmation of human dignity; they feed our spirits and comfort us even as they call upon us to reimagine or envision finding common ground. Ceremonies validate and legitimize Treaties, family and kinship lines, and connections to the land .

References:

The New Wampum: Respect, Trust and Friendship. 2016. https://qonaskamkuk.com/peskotomuhkati-nation/2016-the-new-wampum-respect-trust-and-friendship/

Truth and Reconcillation Commission of Canada. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1450124405592/1529106060525

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|